Radio Program

Our regular Science and the SeaTM radio program presents marine science topics in an engaging two-minute story format. Our script writers gather ideas for the radio program from the University of Texas Marine Science Institute's researchers and from our very popular college class, Introduction to Oceanography, which we teach to hundreds of non-science majors at The University of Texas at Austin every year. Our radio programs are distributed at to commercial and public radio stations across the country.

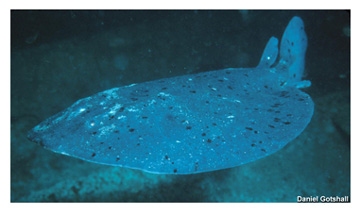

When a fish known as Torpedo californica locates its prey, it glides in slowly. When it’s within a few inches, it lunges, enfolds the prey like a tortilla wrapping around a piece of skirt steak, then stuns it with an electric shock of up to 50 volts.

If you dive a few hundred feet into any ocean and shine a flashlight into the dark, chances are you’ll see a flurry of small flakes all around you. The flakes are known as “marine snow.” They’re not flakes of frozen water, though, but slimy clumps of small organisms and other matter that are falling toward the ocean floor. They’re an important source of energy for life at greater depths, and they help reduce global warming.

The land often feeds the sea. Nutrients from the land wash into the sea, where they support the tiny organisms that form the first link in the food chain. In some places, though, it works the other way around -- the sea provides the nutrients to support life on land.

The next time you walk barefoot on the beach, and let the wet sand squish between your toes, think about this: You might be walking through the homes of thousands of tiny creatures.

The oceans are the cradle of life. The first known life on Earth appeared in the oceans at least three and a half billion years ago -- a type of one-celled organism known as cyanobacteria. They gave rise to more complicated lifeforms later on. And they also helped make modern-day life possible by pumping oxygen into the air and water.

Most fish keep a diary. It records their motions through the seas. It can tell us whether they swam through polluted waters, and sometimes even what the water temperature was.

Today, just about everybody understands the dangers of DDT. The pesticide was used around the country in the 1950s and ’60s to kill mosquitoes. But it also killed birds and other wildlife, and caused health problems in humans. So the environmental harm outweighed the benefits.

You can’t tell by looking, but New York City is at the head of one of the world’s most impressive canyons -- the Hudson Canyon. From the mouth of the Hudson River, it extends about 300 miles into the Atlantic Ocean, and cuts almost four miles deep into the continental shelf. It’s a conduit for moving sediments, nutrients, and pollution from the land to the deep ocean.

If you’re a mussel -- of the edible aquatic variety -- then you’d better be on your best behavior: Big Brother is watching you. In fact, a federal research group has been keeping an eye on mussels and oysters for more than two decades -- from Puerto Rico to the Great Lakes to Alaska and Hawaii.

Some of the tiniest creatures in the ocean play a big role in controlling our planet’s temperature. But as the temperature goes up, the overall volume of these creatures appears to go down, which reduces their ability to keep Earth from overheating.