Most fish keep a diary. It records their motions through the seas. It can tell us whether they swam through polluted waters, and sometimes even what the water temperature was.

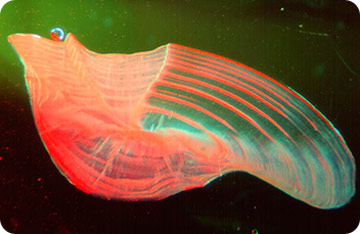

This little diary is called an otolith -- an “earstone.” It’s a small pebble of calcium carbonate that grows in the inner ear. It’s found in all fish except sharks, rays, and lampreys. Depending on the species of fish, it can grow up to an inch in length.

The otolith is part of a fish’s ear. Together with tiny hairs around the otolith, it helps the fish hear and stay upright. In fact, most fish have pretty good hearing, which helps them locate mates and prey, and stay away from danger.

For marine scientists, though, the otolith serves another important function: It records information about a fish’s life.

The otolith grows like tree rings. In very young fish, new layers typically are deposited every day. These layers contain not only the stony material, but chemicals from the water, including pollutants. Careful analysis can allow a researcher to map out a fish’s path over several months -- information that can help develop plans for protecting a species’ nursery habitat.

Slicing through an otolith can reveal a fish’s age. Using this technique, researchers have found that many species live to be 20 to 30 years old, and some can reach 50 years or more. Information about every one of those years is recorded in the fish’s own little diary: an otolith.

copyright 2007, The University of Texas Marine Science Institute