Radio Program

Our regular Science and the SeaTM radio program presents marine science topics in an engaging two-minute story format. Our script writers gather ideas for the radio program from the University of Texas Marine Science Institute's researchers and from our very popular college class, Introduction to Oceanography, which we teach to hundreds of non-science majors at The University of Texas at Austin every year. Our radio programs are distributed at to commercial and public radio stations across the country.

Trillions of metallic nodules cover the bottom of a vast region of the Pacific Ocean. They’re worth a fortune, so mining operations are considering scooping them up. But like many things, the idea is complicated. The nodules are the key to survival for many species of life. So taking the nodules away could cause massive loss of marine habitat.

Atlantic menhaden stinks. Because of that, its oily flesh isn’t exactly a sought-after treat. Over the decades, though, it’s been a common sight on American dinner tables -- in margarine, salad dressing, cookies, and other products. It’s also been used to feed pets, other fish, and even plants. In fact, menhaden is one of the most economically important fish in American waters.

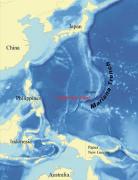

In November of 1520, an expedition led by Ferdinand Magellan headed into an ocean that was a complete mystery to European sailors. It turned out to be far larger than they expected -- and far calmer. It was so calm, in fact, that they called it the Pacific -- a name that means “peaceful.”

Magellan’s expedition was backed by the king of Spain. It was looking for a new route to the Spice Islands -- part of modern-day Indonesia, in the western Pacific. Previous journeys to the islands went around the tip of Africa and across the Indian Ocean.

The sand striker is like something out of a nightmare. The worm hides in the sediments on the sea floor, then lunges out to grab a passing fish or crustacean. It clamps its jaws together so fiercely that it can snap the prey in two. It’s even been known to inflict nasty bites on people.

When Robert Wyland was 14 years old, he and his mother traveled from their home in Michigan to Laguna Beach, California. From the water, Wyland saw another mom and child taking a trip: a gray whale and her calf, headed toward Mexico. That inspired a life-long interest in whales, and a decades-long public art project -- the Wyland Whaling Walls.

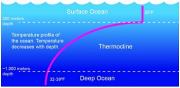

The waters of most of the world’s oceans are stacked like the layers of a cake. Each layer is a different temperature. The top layer is warm, the bottom layer is cold, and the layer in the middle is a transition zone -- the region with the biggest change in temperature.

That layer is known as the thermocline. It begins a few hundred feet below the surface, and can extend downward for a few thousand feet.

When sheep or cattle burp, it’s not just rude -- it’s a hazard. The average dairy cow can belch almost 400 pounds of methane per year. And methane is a powerful greenhouse gas -- 28 times more effective at trapping heat than carbon dioxide is. So sheep and cattle account for up to 20 percent of global climate change.

One way to cut that amount may be to feed them seaweed. A small amount mixed into the diet can almost completely eliminate the methane the animals produce.

In Greek mythology, Hades was the underworld -- the dark realm of the dead. And that seemed like a good description of the deepest parts of the ocean. They’re dark, and until fairly recently were thought to be lifeless. So scientists called the region below about 20,000 feet the hadal zone, after Hades.

It turns out, though, that the hadal zone is a lot livelier than expected. Biologists have discovered more than 400 species there -- fish, shellfish, worms, snails, and others. They’ve also found thriving colonies of microorganisms in the sediments.

People who picnic on the beach sometimes face a greedy pest: a seagull. Gulls grab the food around people -- and have even been known to take it right out of an eater’s hands. And some recent research says that’s no coincidence -- the gulls appear to prefer food that’s been handled by humans.

Scientists at Exeter University checked out the preferences of herring gulls on the southwestern coast of England. They offered the gulls a choice of two Ma Baker’s blueberry bars, which are wrapped in bright blue packaging.

Clear skin is worth some extra time -- even for a whale. In fact, some whales may leave their usual feeding grounds for weeks to clear up their skin.

Many whales found in cold polar waters have sickly looking skin. It’s covered by a slimy yellow layer of algae. But the skin of other whales in the same areas looks clear and healthy.

Whales that spend most of their time in polar waters sometimes head for the tropics. The leading ideas have said the trips provide access to better feeding grounds, or protection for calves.