Radio Program

Our regular Science and the SeaTM radio program presents marine science topics in an engaging two-minute story format. Our script writers gather ideas for the radio program from the University of Texas Marine Science Institute's researchers and from our very popular college class, Introduction to Oceanography, which we teach to hundreds of non-science majors at The University of Texas at Austin every year. Our radio programs are distributed at to commercial and public radio stations across the country.

You can’t hide from satellites -- especially if you stain the ground with large patches of poo. Of course, it helps if the ground is the pure white snow and ice of Antarctica.

Scientists have used these brown stains to locate more than half of the colonies of emperor penguins. Because a colony can contain thousands of penguins, the patches of poo can be quite large.

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons -- PAHs -- are compounds that can be both good and bad. On the good side, they form the “bark” on a slice of brisket, which adds flavor. On the bad side, they can cause cancer, so it’s best to avoid them.

PAHs are also bad for young fiddler crabs. In combination with direct sunlight, in fact, they’re killers.

Dozens of mermaids MERMAIDS drift with the currents of the South Pacific. They listen for the rumble of earthquakes on the ocean floor. Then they pop to the surface to tell seismologists what they’ve heard.

These MERMAIDS don’t have flippers, though. They’re scientific devices: Mobile Earthquake Recorder in Marine Areas by Independent Divers -- MERMAIDS.

Seismologists record earthquakes to learn what’s happening below Earth’s surface. Sound waves bounce around inside the planet. Recording those waves from many locations allows the scientists to map what’s below the surface.

Just because something is tiny doesn’t mean it’s defenseless. Some of the smallest organisms in the oceans, for example, have found ways to keep much larger organisms from gobbling them up.

Researchers have studied how some types of algae and other organisms protect themselves from predators known as copepods. These are tiny shrimp-like creatures that are common in the top layers of the oceans. C

When you’re being chased by a great hammerhead shark, simply running away isn’t always a great option. The shark is big and fast, so there’s a good chance it’ll catch whatever it chases. So the best plan is to run to someplace where the sharks can’t follow -- like shallow water.

Adult blacktip sharks on the southeast coast of Florida seem to have adopted that strategy. Researchers saw them do it in three videos shot with drones in 2018 and ’19.

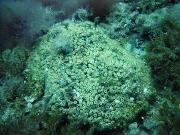

Warmer oceans are bad news for corals. Higher temperatures can kill the living part of a coral, leaving only a bleached-out skeleton. Despite appearances, though, one species of coral might not be dead at all -- it might be only mostly dead. And when conditions improve, it can regenerate.

Researchers studied a type of coral found only in the Mediterranean Sea. In particular, they regularly checked on a large patch of coral off the coast of Spain from 2002 through 2017.

Shortly after the end of World War II, American forces on Kwajalein Atoll, a small island in the western Pacific Ocean, faced a problem. It would cost more to ship leftover airplanes to salvage yards than the planes were worth. So more than a hundred Corsairs, Wildcats, Avengers, and other warplanes were loaded onto barges, carried into the middle of the lagoon, and dumped.

Today, most of them are encrusted with corals and surrounded by fish and other marine life -- artificial reefs that have been growing for 75 years.

Adelie penguins live in one of the iciest regions on Earth -- on the rim of Antarctica. But when the ice around one colony thinned out a few years ago, the penguins flourished. The adults grew fatter and the chicks were more likely to survive.

Adelies are among the smallest penguins in Antarctica. A typical adult is up to a couple of feet tall and weighs about 10 to 12 pounds. They’re also the most common penguins on the continent -- they form colonies of thousands of birds all around it.

If you live along the coast, you might get hit by several tsunamis a year -- but not even know it. They aren’t generated by underwater earthquakes, volcanoes, or landslides. Instead, they’re caused by the weather. So they’re called meteorological tsunamis -- meteotsunamis, for short. And they may be pretty common.

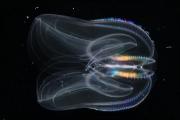

The sea walnut first entered the Baltic Sea almost 40 years ago, probably hitchhiking on cargo ships. Since then, this little critter has been a big pest. The population has exploded as the organisms have gobbled up young fish and crustaceans. And to sustain themselves during the winter, they may eat their own young.