Radio Program

Our regular Science and the SeaTM radio program presents marine science topics in an engaging two-minute story format. Our script writers gather ideas for the radio program from the University of Texas Marine Science Institute's researchers and from our very popular college class, Introduction to Oceanography, which we teach to hundreds of non-science majors at The University of Texas at Austin every year. Our radio programs are distributed at to commercial and public radio stations across the country.

For the seagrass beds of southern Texas, rising sea level may be a case of give and take—or make that take and give. Higher waters are killing off some seagrass. But as the water rises even higher, newly submerged land has the potential to increase the total seagrass area.

Seagrass is important for many coastal ecosystems. It can protect the coast from storms, filter pollution from runoff, and provide habitat and food for fish and other life. So losing seagrass is a big deal.

The “beards” of marine mussels aren’t just a fashion statement. They anchor the mussels to the sea floor, attach to each other to form large “beds,” and hold out potential invaders. They’re also playing a role in materials research—scientists study the beards to learn how to make water-proof glue for many applications.

The beards consist of a bundle of about 20 to 60 threads known as a byssus. The threads radiate outward from the mussel’s “foot.” Each thread is tipped with a biological superglue—a combination of proteins from the mussel and metals from the water.

Early in World War II, the Navy began using sonar to probe for enemy U-boats. Ships would send out pulses of sound, then measure their reflection to figure out what was below. But early observations revealed something a little disconcerting: The ocean floor wasn’t where it was supposed to be—it was a lot closer to the surface. Sonar operators thought they might be seeing uncharted underwater islands.

Pufferfish in Japan are known for one thing. They’re a delicacy that can be deadly. Their organs contain a highly toxic compound that can kill in minutes. But one species of pufferfish has a different distinction: Its males might be the most creative artists in the oceans.

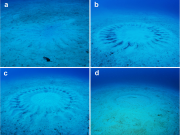

In 1995, divers off the coast of Japan saw an unusual pattern in the sand on the ocean floor—a circle with small peaks and valleys radiating out from a flat center. It wasn’t until 2011 that marine scientists could explain them: the creations of a species known today as white-spotted pufferfish.

As Earth gets warmer, scientists expect to see some changes in hurricanes. There might not be more of them, but the strongest ones might be much more intense.

To better understand what might happen, scientists are digging deep into the past. They’re looking at how often especially powerful hurricanes made landfall when climate conditions were similar to what we’re seeing today.

Until 2011, no one knew that a couple of groups of dolphins found along the coast of southeastern Australia were a separate species from all other dolphins.

Burrunan dolphins are related to the two other known species of bottlenose dolphins. There are two groups of Burrunans—about 250 dolphins in all.

But today, no one knows how much longer the species might be around. It’s critically endangered. And it’s threatened by several hazards, including industrial chemicals. In fact, the species contains higher levels of one group of chemicals than any other dolphins in the world.

“Million Mounds” may be overstating the case a bit, but there’s no doubt it’s one of the most extensive deep-water coral reefs on the planet. Or make that part of one. Scientists recently discovered that the system extends far beyond Million Mounds—the biggest deep-water coral reef yet seen.

The entire complex stretches along the southeastern Atlantic coast of the United States. It’s a few dozen miles out, from Miami to near Charleston. It encompasses about 50,000 square miles, at depths of about 2,000 feet or greater.

For a tiny marine worm found in the Bay of Naples and elsewhere, life ends in a frenzy. The worms lose a lot of their internal organs, their eyes get bigger, and they rise to the surface. There, as they paddle furiously, they release sperm and eggs, creating the next generation. And it’s all triggered by moonlight.

Conditions in the Arctic Ocean may be about to switch gears. That could mean that Arctic waters would become more like those in the North Atlantic—a process known as “atlantification.” As a result, sea ice would disappear a lot faster than it has in recent years.

The rate of sea-ice loss peaked in 2007. The total amount of ice is still going down, but much more slowly than it was before. In December of 2023, in fact, the sea ice increased at a higher rate than in all but two other months in the past 45 years.

Some tiny sea snails may look like angels, but they act more like little devils. They rip their favorite prey from their shells. And the prey just happens to be a relative.

Sea angels are found around the world, from the arctic to the tropical waters near the equator. Most range from the surface to depths of a couple of thousand feet, although some have been seen more than a mile down.