Radio Program

Our regular Science and the SeaTM radio program presents marine science topics in an engaging two-minute story format. Our script writers gather ideas for the radio program from the University of Texas Marine Science Institute's researchers and from our very popular college class, Introduction to Oceanography, which we teach to hundreds of non-science majors at The University of Texas at Austin every year. Our radio programs are distributed at to commercial and public radio stations across the country.

Thresher sharks are some of the “snappiest” fish in the oceans. They have an oversized tail fin that looks like a scythe—and is almost as deadly. A shark “snaps” the fin like someone snapping a towel in a locker room, stunning its prey. And a recent study worked out some of the details on how the shark does it.

Threshers are found around the world. Most stay fairly close to shore, and not very deep. Adults can grow to about 20 feet long.

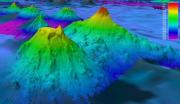

It may sound surprising, but many mountains are hiding from us—some of which may be more than a mile high. Scientists are finding more of them all the time, though—at the bottom of the sea. A research cruise in 2023, for example, found four of them in the Southern Ocean.

When you build a house, it affects the surrounding ecosystem. The same thing applies to houses built by fiddler crabs in salt marshes. Their burrows can help or hinder the surrounding plants, affect the flow of water, and perhaps cause the marsh to send more greenhouse gases into the air. Thanks to all of that, fiddlers are sometimes described as “ecoengineers.”

In 1875, Navy lieutenant commander Charles Dwight Sigsbee and his ship, the George S. Blake, began a journey into the history books. They started measuring the depth of the Gulf of Mexico with a mechanism that Sigsbee created. When the job was finished three years later, the ship had measured the entire Gulf—the first ocean basin to have an accurate map of all its contours.

Olive trees are sprouting all across the Balearic Islands—a chain off the Mediterranean coast of Spain. The largest island, Mallorca, has more than 800,000 cultivated trees. They yield a good portion of the world’s supply of extra virgin olive oil.

The classic example of chaos theory is called the butterfly effect: If a butterfly flaps its wings over China, it creates ripples in the air that might eventually trigger storms over the Americas. Something similar may be playing out over the South China Sea and the surrounding land: Changes in climate conditions there may influence the rest of the world.

If you’re afraid of the dark, you should avoid the “midnight zone” in the oceans. It’s so far down that no sunlight ever reaches it. The zone’s inhabitants include creatures with bulging eyes and big, sharp teeth, and some with bright, wiggling “lures” to attract prey.

One inhabitant also looks like the stuff of nightmares, but it’s a threat only to small fish and other tiny creatures: Stygiomedusa gigantea—the giant phantom jelly. Its “body”—known as a bell—is about three feet across. It can expand to several times that size, though, perhaps to wrap up its prey.

In a classic Jules Verne novel, the submarine Nautilus travels “20,000 leagues under the sea.” You might think that “20,000 leagues” indicated the sub’s depth. But you’d need a really deep ocean for that: a league is three miles, so 20,000 leagues is 60,000 miles. The title tells us how far the Nautilus traveled through the oceans.

Over the centuries, sailors and mapmakers created new units of measure, with new words to describe them, for plying the world’s oceans. Some of the words have been heaved overboard, but some are still in use.

The telescopefish has a cast-iron stomach. Not only can the stomach digest prey that’s bigger than the telescopefish itself, but it’s as dark as cast iron. That prevents the fish’s prey from getting revenge by attracting critters that might eat the telescopefish.

There are two known species of telescopefish. Members of both species are small—no more than about six to eight inches long. They’re found in fairly warm waters around the world, at depths of a third of a mile to a mile and a half or so.

From poetry to music to movies, we’re always hearing about the “deep blue sea.” But the seas aren’t always deep blue. And sometimes, they’re not blue at all. They can be green, brown, or other colors. And each color can tell us something about what’s happening in that part of the sea.

Understanding what the colors are telling us is one goal of PACE—Plankton, Aerosol, Cloud, Ocean Ecosystem—a NASA satellite that launched in February.