Radio Program

Our regular Science and the SeaTM radio program presents marine science topics in an engaging two-minute story format. Our script writers gather ideas for the radio program from the University of Texas Marine Science Institute's researchers and from our very popular college class, Introduction to Oceanography, which we teach to hundreds of non-science majors at The University of Texas at Austin every year. Our radio programs are distributed at to commercial and public radio stations across the country.

It looks like something out of a cartoon -- a tool to help Popeye cut open a can of spinach, for example. But the sawfish is a real creature, and it uses its long, toothy “saw” to dig up its own meals.

There are actually two kinds of fish with saws. One is the sawshark. It’s a true shark, with a streamlined body and gills on its sides. A typical adult is about 3 to 5 feet long. The other is the sawfish -- a type of ray with a flattened body and gills underneath. It’s much bigger than the sawshark -- up to 20 feet or more.

As fall gives way to winter in the southern hemisphere, one of the world’s largest migrations churns the waters off the southeastern coast of Africa. Sardines -- about 30,000 tons of them -- follow the current to warmer waters. Sharks and dolphins herd groups of the fish, penguins pick them off from below and seabirds from above, and whales gulp down gigantic mouthfuls.

Dolphins are some of the smartest animals on the planet. So when it comes to finding its way through the water, it’s not surprising that a dolphin uses the ol’ melon. In this case, we mean it literally. There’s a structure in the dolphin’s head that’s called a “melon.” It produces sounds that the dolphin uses to locate food, predators, and other objects in its path.

Every summer, more than 6,000 square miles of the Gulf of Mexico turns into a dead zone. The Mississippi River dumps massive amounts of nutrients into the Gulf -- mainly fertilizers and animal waste from farms and ranches. That starts a chain reaction that consumes most of the oxygen at the bottom, killing off most of the shrimp and oysters that live there.

This process isn’t good for fish, either. In fact, studies are showing that some fish stop reproducing. It may be part of a natural defense mechanism that gets out of hand.

After pirates and rising fuel prices, a ship owner’s worst enemy just might be a creature that’s not much bigger than a quarter: the barnacle. When enough of them glom onto a ship’s hull, they slow the ship down and cut its fuel efficiency by up to 25 percent.

A walrus is a big pile of blubber. That’s not an insult -- it’s a matter of survival. During the winter, blubber can make up up to a third of a walrus’s body mass. That keeps the walrus toasty warm as it slices through frigid waters.

Blubber is just one way that marine mammals keep warm. Others include dense fur and tapered bodies. And if all else fails, they can always do what snowbirds everywhere do and flee to a warmer climate.

We all know that sea monsters are nothing more than legends, right? And yet, some of the creatures in the ocean depths sure look like sea monsters -- like something out of a nightmare -- or at least a bad movie.

Even if you’ve never visited Norway, one word is likely to conjure images of beautiful Norwegian coastlines: fjords. These deep canyons are found around the world, but perhaps because of the name -- a Norse word that means “place where you cross over” -- they’re most associated with Norway.

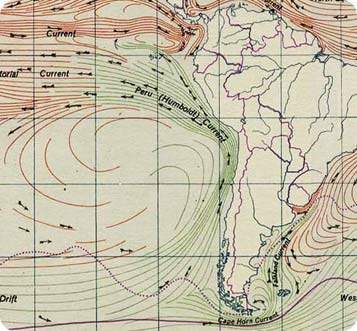

A cold, slow current along the Pacific coast of South America nurtures one of the most productive fisheries in the world. Anchovies, sardines, mackerel, squid, and a host of other creatures thrive in its nutrient-rich waters.

If you’re not a fan of anchovies, then the Pacific Coast of South America isn’t for you. A large fraction of the world’s anchovies are caught in the cold waters off Peru and Chile. They’re sustained by an ocean current that creates the most productive fisheries in the world.