Radio Program

Our regular Science and the SeaTM radio program presents marine science topics in an engaging two-minute story format. Our script writers gather ideas for the radio program from the University of Texas Marine Science Institute's researchers and from our very popular college class, Introduction to Oceanography, which we teach to hundreds of non-science majors at The University of Texas at Austin every year. Our radio programs are distributed at to commercial and public radio stations across the country.

Five and a half million years ago, the Mediterranean Sea was little more than a giant hole in the ground. Cut off from the Atlantic by a rock wall across the Strait of Gibraltar, it dried up. The little water that remained was so salty that almost nothing could live in it, and its surface was perhaps a mile or more below the level of the Atlantic.

But soon after that, things began to change. A recent study says the Mediterranean refilled first with a trickle, then with one of the greatest floods our planet has ever produced.

Over the last decade, marine scientists have been busily counting the organisms in the oceans. And not surprisingly, they just don’t have enough fingers and toes to add them all up. They’ve already announced thousands of possible new species, and should add many more to the list when they report on the Census of Marine Life this fall.

The list of possible new species includes jellyfish, sponges, shrimp, crabs, and many others. One example is a relative of the jellyfish known as a comb jelly.

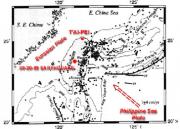

It’s hard to think of a typhoon as a life-saver. In the western Pacific, these giant storms kill thousands every year, and cause billions of dollars in damage. Yet in Taiwan, they may actually save lives: Research shows they may help prevent monster earthquakes.

“Typhoon” is just another name for a hurricane. It’s a giant tropical storm that can pack strong winds, heavy rains, and a massive storm surge -- not something you want to mess with.

The Arctic tern doesn’t look like a marathon winner. The bird is about a foot long and weighs just a few ounces. Yet this little dynamo spends a third of each year trekking between the Arctic Circle and the Antarctic Circle -- a twisting round-trip of almost 45,000 miles. That’s by far the longest known migration path of any bird.

The Arctic tern breeds at high northern latitudes -- from Alaska and Canada to Greenland, Scandinavia, and Siberia. When the northern summer draws to a close, though, it heads south.

Sometime in the not-too-distant future, small submersibles might patrol the world’s oceans for months or years at a time. They’ll monitor temperature, salinity, currents, and other conditions. And they won’t need to gas up their engines or replace their batteries during those long cruises, because they’ll get their power from the oceans.

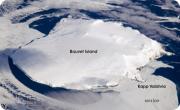

If you want to get away to get away from it all, forget the Caribbean, the South Pacific, or even the South Pole. We’ve got a place that beats them all: Bouvet Island, a small outcropping of rock and ice in the Southern Ocean. The nearest land is more than a thousand miles away, making Bouvet the most remote island on the planet.

The marine organism known as Alexandrium tamarense looks harmless enough. Its microscopic body is round or walnut-shaped, and is generally colored brownish-orange. Get enough of these little guys together, though, and you’ve got big trouble.

Alexandrium creates what scientists call “harmful algal blooms,” which often lead to red tides. Here in the United States, Alexandrium is found on both the Atlantic and Pacific coasts.

The brown pelican is a common sight around piers and docks along much of the American coastline. But that wasn’t the case a few decades back -- the bird was on the verge of disappearing.

Even to the untrained eye, it’s obvious that the waters of the world’s oceans aren’t the same. The crystalline waters of the Caribbean don’t look at all like the muddy waters off the mouth of the Amazon River.

The difference isn’t limited to the surface, though. In fact, different water masses are stacked atop each other like the layers of a cake.

For a shark, retirement paradise isn’t Florida. Instead, it just may be one of two small island-nations that recently banned shark fishing from their territorial waters.