Radio Program

Our regular Science and the SeaTM radio program presents marine science topics in an engaging two-minute story format. Our script writers gather ideas for the radio program from the University of Texas Marine Science Institute's researchers and from our very popular college class, Introduction to Oceanography, which we teach to hundreds of non-science majors at The University of Texas at Austin every year. Our radio programs are distributed at to commercial and public radio stations across the country.

A hurricane is like a giant power plant. In a single day, a run-of-the mill hurricane can produce 200 times as much energy as all the power plants in the entire world. And a major hurricane can produce several times more.

It might not sound right, but only about one percent of that comes from a hurricane’s winds. That’s still a lot of power—the equivalent of a 10-megaton H-bomb every 20 minutes.

Nobody likes the booms and cracks of pile drivers and airguns. They’re not only aggravating, but they can cause hearing loss and other health problems. So there are laws and regulations to control how those tools can be used.

There are similar regulations to protect the ears of marine mammals in offshore construction zones. The noise is an extra problem in the oceans because sound carries a lot farther underwater than in the air.

The giant oceanic manta ray is one of the most graceful fish on Earth—and one of the biggest. Its “wings” can span 20 feet or more. It flaps them gently as it glides through the ocean.

The rays generally are found in groups of no more than a thousand or so. Yet scientists recently discovered the largest congregation of them ever seen, off the coast of Ecuador—an estimated population of more than 22 thousand.

Many species of marine life are spread far and wide—across millions of square miles. But others are concentrated in patches no bigger than your backyard garden. And thousands of species can share the space.

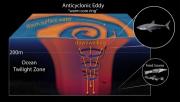

If you’re one of the ocean’s major predators, you go where the food is—even if it might make you a little dizzy. Scientists recently found that tunas, sharks, and other big fish were more common inside eddies in parts of the Pacific Ocean than in the surrounding water. And not surprisingly, that’s where the food was.

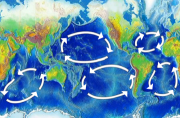

Much of the water in the world’s oceans is herded like cattle being driven to market—not by cowboys on horseback, but by strong currents. Known as gyres, they help control global temperatures and the nutrients available in different parts of the oceans. They also round up floating debris, forming giant garbage patches.

Green doughnuts are typically something you want to avoid. But some giant green doughnuts on Australia’s Great Barrier Reef may actually be good for us. They may store carbon on the ocean floor. That keeps it out of the atmosphere, where it would add to climate change.

You might want to save those leftover egg whites at breakfast. Researchers at Princeton University found a way to use them to filter salt and tiny bits of plastic from sea water. It’s a method that could be cheap and reliable, and could be used on a large scale.

The team was trying to mix up a new recipe for aerogel—a material that’s mostly air or other gas. It’s extremely light weight, but it’s versatile. It’s used for insulation, water filtration, and even to catch bits of comet dust.

If sharks had dentists, one might want to set up shop at Muirfield Seamount, near a set of islands in the Indian Ocean. A recent expedition there pulled up a haul of more than 750 shark teeth—the largest ever seen at a single site. Most of the teeth came from modern-day species. But a few belonged to the ancestors of megalodon, which died out millions of years ago.

Young killer whales off the coast of Washington and British Columbia like to nip at each other. That leaves white scars on their backs and sides—but they’re not permanent. That allows biologists to use the scars to learn about the life histories of these endangered animals.

They’re looking at southern resident killer whales—the smallest of the four types of resident killer whales. There are only 73 known members. They live in family groups, with the offspring staying with their mothers all their lives.