Radio Program

Our regular Science and the SeaTM radio program presents marine science topics in an engaging two-minute story format. Our script writers gather ideas for the radio program from the University of Texas Marine Science Institute's researchers and from our very popular college class, Introduction to Oceanography, which we teach to hundreds of non-science majors at The University of Texas at Austin every year. Our radio programs are distributed at to commercial and public radio stations across the country.

Oil and gas bubble up through the ocean floor all the time. They form oil slicks, create tar balls that wash up on shore, and make pillows of methane ice. And in some rare instances, they form asphalt volcanoes—tall, black mounds with smooth sides.

The first were discovered in 2003, about two miles deep in the Gulf of Mexico. Others have been found in the Gulf since then, along with a few off the coasts of California and western Africa. Some of those in the Gulf of Mexico have split apart, creating shapes that look like the fronds of a palm lily, so they’re called tar lilies.

Good news for one species isn’t necessarily good news for all. Consider the wildlife on Pleasant Island, off the coast of southeastern Alaska. Sea otters returned to the island a couple of decades ago. Gray wolves came along a decade later. The wolves ate most of the island’s deer, then started hunting the otters. That’s good for the wolves, but bad news for everyone else.

Millions of residents chased out of their homes. Trillions of dollars in extra damages. A tenth of coastal crops destroyed. That’s what some developing countries could face from coastal flooding by the year 2100, according to a recent study. Several regions could be especially hard hit, facing costs of more than five percent of their total economies.

Here’s a pop quiz for you: How many tentacles does an octopus have? If you said “eight,” sorry, but you fail. An octopus does have eight limbs. But technically, they’re known as arms, not tentacles.

An octopus is a cephalopod—a group that includes squid, cuttlefish, and nautilus. Each of them has a whole bunch of limbs—from eight for the octopus, to more than 90 for the nautilus. The animals use those limbs to look for and catch prey, to move along the sea floor, and even to build houses.

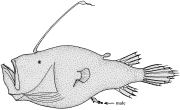

When scientists began pulling anglerfish from the deep ocean, they noticed something odd—all of the specimens were female, and many of them had small parasites attached to their bodies. And when they studied the fish in detail, the story got even odder—the “parasites” were actually the missing males.

When neighborhoods start to go downhill, people move away. And today, that’s happening in marine neighborhoods. As the oceans get warmer—a result of our changing climate—fish and other critters are moving out of their neighborhoods and into cooler waters. That includes the tiniest organisms, known as plankton. And a recent study says the trend could accelerate in the decades ahead.

Tiger sharks can boldly go where no diver has gone before—or is likely to go anytime soon. That makes them great research assistants for marine scientists. In fact, they helped confirm the discovery of the largest known seagrass meadow in the world.

The seagrass is in the Bahamas. Scientists used satellite observations to get a rough estimate of the size of the beds. Divers took more than 2500 plunges into the clear, shallow Caribbean waters to confirm the satellite maps.

Many Americans have learned a new term in the past few years: atmospheric river. Massive ribbons of water vapor have brought floods and epic snowfalls to the West Coast. And our warming climate could produce more intense examples in the years ahead.

An atmospheric river begins as warm ocean water evaporates and climbs into the sky. It forms a stream of water vapor that surfs along with the weather. It can be a few hundred miles wide and a thousand miles long, and carry several times more water than the Mississippi River.

A few years ago, some scientists in Australia got a tip from a city council member in a town in the state of Queensland, on the country’s northeastern coast: Some unusual spiders were appearing on the beaches of a nearby town during especially low tides.

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch isn’t what you think. It’s often depicted as a big “island” of junk—plastic bottles, fishing nets, sneakers, tires, and other debris. But that’s not the case. In fact, you could sail right through it and never even notice. That’s because, instead of an island, it’s more of a “soup”—tiny bits of plastic and other debris spread across an area twice the size of Texas, from the surface to depths of hundreds of feet.