Radio Program

Our regular Science and the SeaTM radio program presents marine science topics in an engaging two-minute story format. Our script writers gather ideas for the radio program from the University of Texas Marine Science Institute's researchers and from our very popular college class, Introduction to Oceanography, which we teach to hundreds of non-science majors at The University of Texas at Austin every year. Our radio programs are distributed at to commercial and public radio stations across the country.

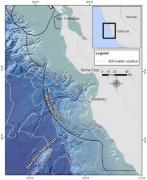

Volcanic mountains dot the west coast of the United States. Some are dormant, some are extinct — and some hide below the surface of the Pacific Ocean.

These underwater mountains are known as seamounts. And the first one ever listed as a seamount lies about 75 miles southwest of Monterey, California. It was discovered in 1933, and a few years later it was named for George Davidson, a leader in exploring America’s Pacific coast.

You could forgive the fin whale if it has an inferiority complex. It’s the second-largest animal on the planet, yet it’s virtually unknown. It’s overshadowed by its bigger cousin, the blue whale. And that’s a shame, because it’s a beautiful and graceful animal.

The fin whale is found around the world, mainly in colder waters. A northern species rings the northern Atlantic and Pacific oceans, while a southern species is found around Antarctica. The northern whales grow up to about 75 feet long, while the southern ones can be about 10 feet longer, and can weigh up to 70 or 80 tons.

It’s been decades since any country exploded a nuclear bomb in the atmosphere. Yet many of the byproducts of those blasts are still with us. And one of them helps scientists track ocean currents.

From 1945 to 1980, the world conducted about 500 nuclear tests in the atmosphere, at sites scattered around the world. Most of those sites were in the northern hemisphere, so much of the radioactive debris fell into northern oceans — especially the North Atlantic.

The foam on a latte, or the foamy meringue on top of a lemon pie, can be a delightful treat. The foam on the ocean? Not so much. It contains some ingredients that you don’t want to eat.

Sea foam is created by strong winds. As the wind blows across the water, it creates waves. When the waves ripple and break, they create bubbles of air. But it’s the material that forms the “skin” of the bubbles that can be so unappetizing.

Penguins may look cool, but they never seem to get cold. And recent research has provided some reasons: tiny holes in their feathers, and a special oil that acts as a sort of antifreeze.Researchers compared the feathers of two types of penguins — the gentoo, which lives in Antarctica, and the magellanic, which lives in the warmer climate of South America.

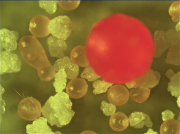

Your shower gel, eye makeup, and even toothpaste may develop a slightly different feel in the years ahead. That’s because the United States has banned one of their key ingredients: tiny balls of plastic known as microbeads.

As the name suggests, most of these beads are microscopic. They’ve been used as abrasives in many personal cleaning products, and as lubricants in many cosmetics. The problem, though, is that when you rinse them off, they don’t stop — they can rinse into rivers, lakes, and all the way into the oceans.

People love sharks. We might be scared of them, but we still love to watch them glide through the water. Most of us watch them on TV, but many prefer to see the real thing — to see their menacing shapes from a boat, or even to plunge in and swim with the sharks.

In fact, shark tourism is big business. And in the next couple of decades, it could become even bigger. As a result, sharks could be worth a lot more alive than dead.

High school science teachers might be looking for some new lab experiments in the coming months. That’s because one of the main supplies for a classic experiment is getting both more expensive and harder to find.

Agar is the gelatin-like substance that’s layered in the bottom of petri dishes. It’s a great material for growing cultures of bacteria and fungi because it stays solid at high temperatures, it’s stronger than gelatin, and the bacteria don’t eat it.

In modern times, salmon from the Pacific Ocean is a delicacy — an expensive dish that’s usually served as a treat — even in areas where the fish is plentiful. In ancient times, though, that wasn’t the case. During spawning runs, tribes and villages caught salmon by the thousands. Many of the fish were preserved, providing nutritious meals during the long, cold winter.

In fact, researchers recently found evidence that settlers in central Alaska were eating one type of salmon about 11,500 years ago. It’s the earliest known instance of people eating salmon in all of North America.

That disturbing packet of goodies that’s stuffed inside many turkeys includes the gizzard — something that few want to eat, but that’s essential to helping the turkey eat. It grinds up food before it passes into the stomach, aiding in the turkey’s digestion.

In fact, the gizzard is a common organ in many types of animals, including some fish and other marine creatures. One is a type of sea slug found in European waters, which feeds on tiny shellfish. And a team of researchers recently dug into its gizzard to find out how it works.