Radio Program

Our regular Science and the SeaTM radio program presents marine science topics in an engaging two-minute story format. Our script writers gather ideas for the radio program from the University of Texas Marine Science Institute's researchers and from our very popular college class, Introduction to Oceanography, which we teach to hundreds of non-science majors at The University of Texas at Austin every year. Our radio programs are distributed at to commercial and public radio stations across the country.

During the 1930s, millions of Americans in the Great Plains saw their farms literally blow away. A deadly drought, combined with poor farming techniques, created the Dust Bowl. Millions of tons of topsoil blew away in black, choking clouds. And that led to a massive migration, as millions of Americans moved west in hopes of a better life.

A new climate-related migration might take place later in this century. Millions of Americans might be forced to flee the coastline because of rising sea levels — the result of our planet’s warming climate.

Imagine skimming across the waves in a long, skinny boat with a few hundred siblings. Some of them paddle, some steer, some throw fishing lines in the water, and the lucky ones get to eat. That’s the life of a siphonophore, an organism that consists of a bunch of smaller organisms all working together as a single colony — and all of them descended from the same egg.

In just about every movie involving a submarine, there’s a dramatic attack scene. The sonar operator monitors the sound of the propellers of ships passing overhead, or sends out a “ping” and listens for its echo off the hull of another sub. He then gives the captain precise details on the location and speed of the enemy vessels.

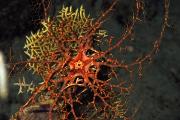

A trip to the grocery store usually requires a basket to hold all the goodies. But a relative of the well-known sea star doesn’t need to grab a basket to hold its groceries — it already has one.

The basket star is found in cold to warm waters in both the northern and southern hemispheres, generally at depths of no more than a few hundred feet. It’s found on the west coast of the United States down to California, and on the east coast down to Massachusetts. It prefers a rocky sea floor, in a spot with a pretty strong current.

It’s hard to think of anything quieter than melting ice. But when the melting ice weighs thousands of tons and is thousands of years old, it can sound like a truckload of Rice Krispies dumped into a swimming pool.

In fact, scientists have found that melting glaciers can be louder than anything else in the oceans — louder even than hurricanes. Glaciers were already known to create some impressive underwater sounds. When a chunk breaks off to form an iceberg, the sound can be heard hundreds of miles away.

Most birds are creatures more of the land or sea than of the air — they spend far more time on the surface than in the sky. But not the frigate bird. It stays aloft for days or weeks at a time. And one species can remain in the sky for up to two months.

For most of the 17th century, the Sun pretty much went to sleep. That appears to have been good news for the ships that plied the waters of the New World. The number of shipwrecks dropped — suggesting that the number and strength of tropical storms went down as well.

To help understand what our planet’s warming climate might mean for future hurricanes, researchers look to the past. Among other things, they study how storm intensity has changed during periods of a warmer or cooler climate.

A species recently discovered in the Antarctic is the anemone equivalent of a bat: it hangs upside down, from the underside of a massive sheet of ice.

In 2013, researchers were testing out a new remotely operated vehicle — a small set of cameras and other instruments at the end of a long cable. The ROV (remotely operated vehicle) was designed to explore waters below the Antarctic ice, which is hundreds of feet thick.

Just because something has never been seen before doesn’t mean it can’t happen in the future. And in the case of hurricanes, what hasn’t been seen before could be especially deadly in the future.

Our planet’s warming climate is forecast to boost the maximum power of hurricanes. That means not only more rain and stronger winds, but higher storm surges. And it could create hurricanes in regions where they’re seldom or never seen.

The oceans transport heat around the globe, keeping the temperatures fairly mild across the entire planet. But a big change in ocean salinity could change that pattern, altering ocean currents and raising global temperatures.

That’s not likely to happen anytime soon. But it could be happening on planets in other star systems. And that could expand the range at which a planet can sustain life.

That range is known as the “habitable zone.” It’s the distance from a star where temperatures are just right for liquid water to exist on a planet’s surface.