Radio Program

Our regular Science and the SeaTM radio program presents marine science topics in an engaging two-minute story format. Our script writers gather ideas for the radio program from the University of Texas Marine Science Institute's researchers and from our very popular college class, Introduction to Oceanography, which we teach to hundreds of non-science majors at The University of Texas at Austin every year. Our radio programs are distributed at to commercial and public radio stations across the country.

We all know that sea monsters are nothing more than legends, right? And yet, some of the creatures in the ocean depths sure look like sea monsters -- like something out of a nightmare -- or at least a bad movie.

Even if you’ve never visited Norway, one word is likely to conjure images of beautiful Norwegian coastlines: fjords. These deep canyons are found around the world, but perhaps because of the name -- a Norse word that means “place where you cross over” -- they’re most associated with Norway.

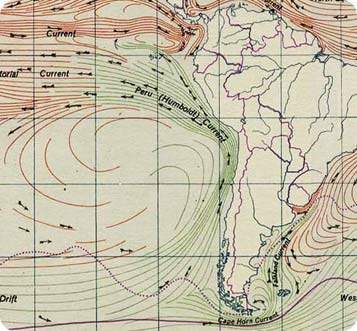

A cold, slow current along the Pacific coast of South America nurtures one of the most productive fisheries in the world. Anchovies, sardines, mackerel, squid, and a host of other creatures thrive in its nutrient-rich waters.

If you’re not a fan of anchovies, then the Pacific Coast of South America isn’t for you. A large fraction of the world’s anchovies are caught in the cold waters off Peru and Chile. They’re sustained by an ocean current that creates the most productive fisheries in the world.

Humpback whales are some of the smartest creatures in the oceans. They sometimes catch fish as teams, and they “sing” complex songs that probably play a role in mating. And their brains have several things in common with the human brain -- including different roles for the two sides of the brain.

Humpbacks are among the oceans’ giants. Adults grow up to 50 feet long, and weigh about 40 tons. They feed by filtering small fish and other organisms from the water.

The Atlantic oyster drill is well named. The inch-long snail climbs on top of an oyster, pours a chemical solvent on the oyster’s shell, then drills a tiny hole. After that, it inserts a tube and sucks out the tasty meat, leaving nothing but an empty shell.

Part of the name, though, isn’t quite as accurate as it used to be. The Atlantic oyster drill has invaded bays along the Pacific coast, too. In California, the snail is plowing through native oysters in a hurry.

When you hold your thumb over the end of a garden hose, the flow changes from a gentle stream to a high-speed jet. The same amount of water is trying to escape through a smaller opening, so it has to move faster.

The same thing happens off the tip of South America. An ocean current that circles the globe squeezes through a 500-mile-wide gap known as the Drake Passage. The current not only speeds up, it also creates powerful eddies. Combined with strong winds and violent storms, that makes the Drake Passage one of the roughest patches of sea on Earth.

It’s as long as a pickup truck and half as heavy. It strikes like lightning, killing with its powerful jaws or dragging its victim into the depths to drown. And it’s not picky about what it eats -- anything from a turtle to a human being suits it just fine.

The nudibranch looks like it ought to be an easy meal for just about any ocean predator. It’s basically a small, colorful, slow-moving blob of flesh with no shell or great big teeth to protect it.

Yet when most predators see a nudibranch, they keep on moving. That’s because the nudibranch’s defense is based on an old principle: waste not, want not. It basically reuses the defense mechanisms of the organisms it eats.

In late 1942, the Queen Mary was carrying 15,000 American troops across the Atlantic to join the war in Europe. German U-boats couldn’t catch her, and even a stiff gale wasn’t a problem for the mammoth ocean liner.

But 700 miles off the coast of Scotland, a wall of water more than 90 feet tall broadsided the ship, almost knocking it on its side. Water poured onto the decks, and just a few more degrees of list would have capsized her. But the Queen slowly righted herself and delivered her passengers to the British Isles.