Radio Program

Our regular Science and the SeaTM radio program presents marine science topics in an engaging two-minute story format. Our script writers gather ideas for the radio program from the University of Texas Marine Science Institute's researchers and from our very popular college class, Introduction to Oceanography, which we teach to hundreds of non-science majors at The University of Texas at Austin every year. Our radio programs are distributed at to commercial and public radio stations across the country.

Blue mussels are riding the winds across the North Sea. They’re not taking up wind surfing, though. Instead, they’re colonizing the bases of offshore wind turbines. Over the next couple of decades, that could boost the mussel population, with ripple effects throughout the ecosystem.

The North Sea is between Great Britain and northern Europe. Winds there are strong and steady, making it an ideal location for wind farms. At the end of 2017, in fact, it was home to about 70 percent of Europe’s offshore wind capacity. And thousands more turbines are scheduled to be installed there.

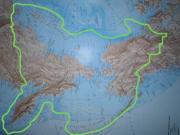

When the glaciers retreated from around present-day Seattle at the end of the last ice age, they left some big holes in the ground. Today, those holes form Puget Sound -- a network of basins and channels in northwestern Washington. The sound is home to an amazing variety of marine life. But the numbers have been dwindling.

Even if you’ve never seen an ocean, you’ve probably felt one -- in the form of rain. A good bit of the rain that falls over land comes from the oceans. Eventually, some of that water makes its way back to the oceans, beginning the cycle all over again.

The blue whale may be changing its tune. Recordings made over the last couple of decades show that the whales are “talking” at a lower pitch. And it’s possible that the changes are intentional.

The world’s largest animal produces a variety of sounds. Some are short -- like individual words or syllables. Others are longer -- “songs” that can be heard for miles. Biologists aren’t sure just what the sounds mean. They could play a role in mating, foraging, or even in keeping a comfortable distance between individuals.

This is a bad time to be a coral reef. In the last couple of decades, rising water temperatures have caused massive “bleaching” events around the globe. That’s killed a large fraction of the world’s reefs. Today, though, marine biologists are looking at ways to give Mother Nature a hand -- in large part by making better coral.

Corals are symbiotes. The coral animals, known as polyps, have colonies of algae living inside them. The algae are protected from predators, and, in return, they produce food for the polyps.

For many people, the rolling and pitching of an ocean-going boat means a quick trip to the medicine cabinet. But for a new type of automated boat, that same motion means free power. The wave action is used to push the boat forward. That could provide a new way for marine scientists to explore the oceans.

Scientists and engineers are experimenting with many ways to propel boats and ships with renewable energy. They’re trying solar and wind power, for example, and breaking apart seawater to power fuel cells.

When parents take their young children to crowded places, they hold hands to help keep the kiddos safe. That’s not a new strategy, though. A tiny marine organism was doing the same thing 430 million years ago.

Scientists found the fossilized organism at the bottom of an ancient sea in England. The creature was an arthropod -- the group of critters that includes insects, crabs, and shrimp. It was about a centimeter long, with a segmented body covered by a hard shell. It used about a dozen pairs of legs to crawl along the sea floor, and long antennas to feel out possible prey.

The ghost pipefish is a master of camouflage. One species looks like blades of seagrass, while another looks like fronds of kelp. And one species piles on several disguises. In fact, the ability to blend in -- to appear and disappear -- earned the ghost pipefish the “ghost” part of the name.

The ghost pipefish is found in warm, shallow waters from the eastern coast of Africa, across the Indian Ocean, to Australia and Southeast Asia. It inhabits everything from coral reefs to seagrass beds. It grows up to a few inches long, with females larger than males.

You’ll find lots of hiking trails along the western coast of the United States. But archaeologists are looking for one more. It might have been hidden for thousands of years -- on the bottom of the Pacific Ocean.

There’s evidence that the first people reached the Americas perhaps 15,000 years ago or even earlier. They came during the last Ice Age, when sea level was hundreds of feet lower than it is today. That exposed a “bridge” of land between present-day Asia and Alaska. People might have crossed that bridge in search of game or other necessities.

Some of the bottlenose dolphins near the town of Laguna, Brazil, seem to have a pretty good thing going. The dolphins herd schools of fish toward spots along the shore. At a signal from the dolphins, fishermen drop their nets into the water. The people trap some of the fish in their nets, while the dolphins get the rest. It’s one of a handful of known examples of humans and wild dolphins working together.