Radio Program

Our regular Science and the SeaTM radio program presents marine science topics in an engaging two-minute story format. Our script writers gather ideas for the radio program from the University of Texas Marine Science Institute's researchers and from our very popular college class, Introduction to Oceanography, which we teach to hundreds of non-science majors at The University of Texas at Austin every year. Our radio programs are distributed at to commercial and public radio stations across the country.

Water, water everywhere -- and not a drop to drink. That’s a key plot point in any tale of survival at sea. Even though the heroes are floating atop an ocean, they can’t drink the water because it’s too salty.

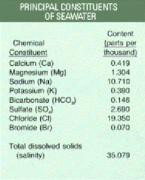

Seawater is about 200 times saltier than freshwater. You’d have to stir a teaspoonful of table salt into a glass of tap water to equal the salt content of the oceans.

Ocean “salt” contains a variety of chemical elements. Sodium and chloride -- the ingredients of common table salt -- account for almost 90 percent of these dissolved elements.

A jellyfish that’s found in the Pacific Northwest seems simple enough. Known as Aequorea victoria, it’s only a few inches across, and it doesn’t sting, so you can float right through it without harm.

Yet a substance that’s produced by the jellyfish has become one of the most remarkable tools in modern medicine and biology -- a tool that earned three scientists last year’s Nobel Prize for chemistry.

The substance is known as GFP -- green fluorescent protein. It produces a faint ring of green light around the rim of the jellyfish’s “umbrella.”

A century and a half ago, biologists got a shock when technicians raised a section of telegraph cable from the bottom of the Mediterranean Sea. The cable had been resting at a depth of more than a mile, where scientists expected to find little or no life. Yet the cable was covered with life: corals, mollusks, worms, and a host of other organisms.

Telegraph cables were responsible for many discoveries about the ocean floor -- from its depth and contours to how it changes.

A tiny fish that’s common in the western Pacific sounds like the James Dean of the oceans: it lives fast and dies young. Known as the pygmy goby, it lives no longer than two months -- a shorter lifespan than that of any other fish.

The pygmy is one of perhaps 2,000 goby species. Some can grow up to two feet long. But the adult pygmy goby measures only about half an inch.

Floating along on its back, using its tummy as a table as it snacks on a clam or scallop, the sea otter is downright adorable.

But all that cuteness masks the fact that the otter is also a hard worker. To survive the frigid waters of the north Pacific, it has to eat about a quarter of its body weight every day, which keeps it busy. And its appetite can help keep coastal ecosystems strong and healthy.

Water covers more than 70 percent of Earth’s surface -- most of it in the oceans. But there’s a debate about where all that water came from. Some scientists say that Earth was born wet, while others argue that the water was dumped here later on.

One key bit of evidence is the ratio of hydrogen to heavy hydrogen in today’s oceans. The ratio varied in different regions of the early solar system. So comparing the ratio found in Earth’s oceans to that of other solar-system bodies could tell us where Earth’s water was formed.

They may not be as famous as the swallows of Capistrano, but some other seasonal visitors are returning to Southern California about now: grunion. The silvery fish pile up on sandy beaches by the thousands, where they lay their eggs before quickly washing back out to sea.

The California grunion is a small fish -- the typical adult is only five or six inches long. It spends most of its life in shallow waters not far from shore, from about San Francisco Bay down to northern Baja.

Contrary to popular belief, you can’t see the Great Wall of China from the Moon. In fact, it’s hard to see even from Earth orbit.

But another “great” structure is easy to see from space. It was built not by human hands, but by nature. It’s the Great Barrier Reef -- the largest living structure on the planet. It stretches more than a thousand miles along the coast of Australia, and covers an area as big as New Mexico.

It’s a jungle out there. Life in the oceans is a constant struggle for survival, with bigger critters eating the smaller ones. It’s not just a struggle of the sharks and fish and crabs, though. It’s a struggle that plays out in every cubic inch of seawater -- enough to make one good mouthful.

The Pacific is the king of the oceans. It’s wider and deeper than the other oceans, and it covers as much area as the Atlantic and Indian oceans combined.

But the Atlantic is gaining on it: It’s growing wider as the Pacific gets narrower. It’s all part of the process that created the ocean basins in the first place.

The basins are the deepest part of the oceans -- a mile and a quarter deep or more. They’re constantly changing as the result of processes below Earth’s surface.