571220-transition zone.jpg

Graph of a typical ocean thermocline. Credit: NOAA

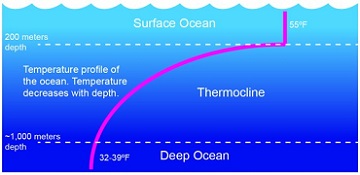

The waters of most of the world’s oceans are stacked like the layers of a cake. Each layer is a different temperature. The top layer is warm, the bottom layer is cold, and the layer in the middle is a transition zone -- the region with the biggest change in temperature.

That layer is known as the thermocline. It begins a few hundred feet below the surface, and can extend downward for a few thousand feet.

The top layer of the oceans is warmed by the Sun. Wind and waves churn the waters near the surface, mixing them up. That transfers the heat downward. The exact thickness of the top layer depends on the amount of sunlight it receives, the strength of the winds, and other factors. Events like El Niño can make it a good bit thicker.

The bottom layer is always cold. Sunlight doesn’t penetrate that deep, and neither does the churning action at the surface. So there’s little difference in temperature from the top of that layer to the bottom. The change in the thermocline, on the other hand, can be pretty dramatic -- 25 degrees or more from top to bottom.

There are actually two types of thermocline. One changes with the seasons. It develops during summer, when the surface is warmer, and vanishes during winter. The other type is there all year long. But it’s not found in all the oceans. Close to the poles, the water is always cold, from top to bottom, so there’s not much layering. Everywhere else, though, the cake is always layered -- with a transition zone in the middle.