A steady breeze across a still pond or lake creates some obvious ripples, as it drags the water along with it. The effect isn’t as easy to see on the ocean, but it’s there nonetheless. In fact, the wind can move so much water that it can cause the layers of the ocean to flip over -- an effect known as upwelling.

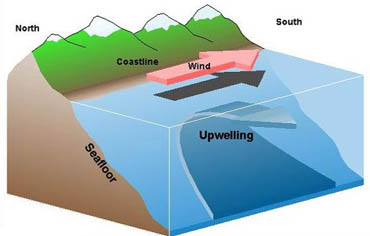

Upwelling brings deep, cold, nutrient rich water to the surface. Credit: Kudzuacres.com

Upwelling brings deep, cold, nutrient rich water to the surface. Credit: Kudzuacres.comIt happens along coastlines and out in the open ocean, along the equator. At the coast, breezes along the shore initially push the water parallel to the shoreline. As the water moves, it’s deflected by the effect of Earth’s rotation. Along the West Coast of the United States, for example, steady northerly winds during summer push the water southward. But it’s deflected to the right by Earth’s rotation, so it moves to the west, away from shore.

As the water at the surface moves outward, water from deeper layers rises to take its place. This water is colder and contains more nutrients, so it creates an explosion of life; more about that on our next program.

Along the equator, trade winds push the water from east to west in both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. The water is pushed to the sides, where Earth’s rotation creates currents that move the water northward in the northern hemisphere, and southward in the southern hemisphere. Just as along the coast, as the surface layers move out of the way, cold, rich waters from a few hundred feet down rise to take their place. As a result, a narrow band along the equator sees a profusion of life -- made possible by a steady ocean breeze.