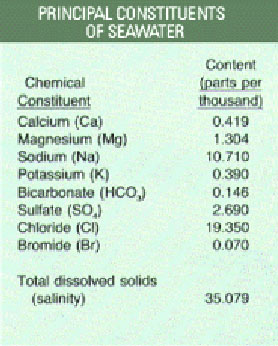

A mouthful of sea water tastes salty. That’s because on average, about three-and-a-half percent of sea water consists of dissolved minerals like chlorine and sodium.

In the open ocean, the concentration of those minerals -- known as salinity -- varies little. But even tiny fluctuations can have a major impact on Earth’s climate.

Principal constituents of seawater. Credit: http://www.palomar.edu/oceanography/salty_ocean.htm

Principal constituents of seawater. Credit: http://www.palomar.edu/oceanography/salty_ocean.htmThat’s because much of the climate is controlled by ocean currents, which carry heat from warmer waters to cooler ones. The currents are influenced in part by the water’s density, which is determined by its temperature and salinity. If the water gets saltier as the result of less rain or greater evaporation, then the currents could be changed. So tracking changes in salinity is a key in understanding changes in the global climate.

Scientists determine the salinity of sea water by measuring how well it conducts electricity; the greater the salinity, the more easily an electric current passes through the water. At sea, this is measured with a device that also measures temperature and pressure.

But measurements taken at sea provide only “snapshots” of conditions at specific locations and times, not a look at the overall oceans. For that, scientists are beginning to rely on satellites. They measure microwave radiation emitted by the oceans. The intensity changes with the level of salinity. This technique will allow scientists to track salinity across the entire globe -- providing one more bit of information in the effort to understand our planet’s changing climate.